The world’s biggest iron ore windfall is fading | Australian Markets

Flying deep into the center of Western Australia, Rio Tinto Group executives, politicians and media step off a chartered jet into a Pilbara airport, little more than a sunbaked shed with steel detectors.

Cameras roll. Smiles flash. They are right here for the revealing of Rio’s Western Range, a new open-cut mine designed to pump out 25 million tonnes of iron ore a yr.

But behind the fanfare, a harsher reality looms: Western Range isn’t about growth. It’s about holding the machine working.

In the Pilbara — home to the world’s largest iron ore output — Rio Tinto is swapping out previous deposits for new simply to take care of present manufacturing.

The powerhouse sector that helped Australia sidestep the 2008 international financial disaster, churned out billionaires, and fed China’s skyline ambitions is no longer booming – it’s plateauing.

Less than two months after the ribbon was cut at Western Range, a more muted signal adopted.

On Wednesday, Rio Tinto reported its lowest first-half earnings in 5 years after iron ore costs slumped. The outcome wasn’t a collapse, however a reminder that the cracks are widening – and the increase years are getting more durable to hold onto.

The steelmaking materials that underpinned Australia’s financial rise is dropping its edge: ore high quality is falling, margins are tightening, and the huge deposits that constructed a long time of prosperity are slowly being exhausted.

None of this can be swift, however the once-reliable useful resource could not be capable of pull Australia by way of the following financial calamity. And there’s not a lot of a fallback plan.

The Pilbara — greater than California — has fuelled the worldwide iron ore trade because the first cargo set sail for Japan almost six a long time in the past.

Warnings of an impending slowdown have surfaced earlier than, just for the industry to show its resilience time and again. But this time, the headwinds are stronger and mining giants are pouring billions into what comes subsequent, because the foundations of the industry start to shift.

“It’s a very significant risk that sits across the Pilbara,” stated Greg Lilleyman, a veteran mining government who served as Fortescue’s chief working officer and spent 26 years at Rio Tinto.

“Customers want higher quality iron ore, lower emissions per tonne of steel, higher productivity from smaller footprints”

The lack of any clear successor to iron ore’s financial heft is leaving a gap that Australia is uncertain how to fill.

As the Pilbara’s dominance begins to wane, broader pressures are mounting: the re-elected Labor authorities is rallying high business leaders to deal with stagnant productiveness with a funds caught in deficit.

The so-called Lucky Country is being pressured to confront the unique irony of its nickname: a nation long-cushioned by useful resource windfalls, now going through the fee of extended complacency.

As China’s starvation for Australian iron ore peaks, Canberra forecasts costs dropping to $US74 a tonne by 2027, round 40 per cent beneath the average price over the previous 5 years.

That spells bother for the federal funds, with income from the sector anticipated to drop by more than $19 billion within the subsequent two years alone. Furthermore, manufacturing volumes are anticipated to peak within three years.

It’s a sharp reversal for a sector that Westpac estimates drove more than half of the nation’s residing requirements features within the first 20 years of the century.

Without main productiveness reform, the bank warns the top of the “mining dividend” may price every Australian $75,000 in misplaced income over the following decade, senior economist Pat Bustamante stated in a July report.

Not everybody is publicly acknowledging the size of the problem.

“Iron ore is the bedrock of Australians’ prosperity and the thread which binds us to the global economy,” Madeleine King, Australia’s minister for assets, advised reporters on the Western Range mine opening in June.

The “project is further proof that Australia’s iron ore sector is the best and most stable in the world.”

Iron ore nonetheless makes up more than 4 per cent of Australia’s financial system and has long been the spine of state and federal budgets.

But holding up manufacturing and funding exploration is getting more durable and more costly as ore high quality declines. At the identical time, steelmakers are beneath strain to cut emissions, accelerating a pivot towards higher-grade ores that produce much less carbon – a lot of it now coming from new mining hubs outdoors Australia.

In West Africa, Guinea’s long-delayed Simandou project, backed by Rio Tinto and Chinese state-linked traders, is lastly nearing manufacturing, with its first cargo anticipated by yr’s finish.

Home to some of the world’s highest-grade untapped iron ore reserves, Simandou spans over 100 kilometres and is projected to supply more than 100 million tons yearly at full tilt.

Australian media has dubbed Simandou the “Pilbara killer” – an overstatement, however one which underscores the stakes. Its development displays Beijing’s long-term ambition: to interrupt its dependence on Australian ore and gain better control over a key enter to its metal industry.

Chinese state-owned firms are more and more partnering with international miners, together with China Baowu Steel Group Corp., which owns 46 per cent of Western Range.

“We are not just unveiling a new operation, we are celebrating the next chapter” within the Baowu partnership, Jakob Stausholm, outgoing CEO of Rio Tinto, stated on the mine’s opening, talking simply meters from a building-sized driverless truck dumping piles of ore into a crusher.

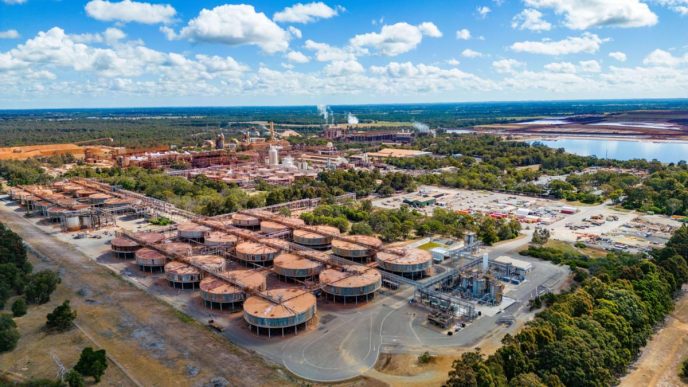

The speeches have been meant to emphasise power and continuity: ore from the new pit was being piled onto an 18-kilometer conveyor belt that might roll all the way in which to Rio Tinto’s current Paraburdoo plant.

But the plant has now been processing materials for half a century – as China diversifies provide and calls for cleaner ore, the Pilbara is beginning to show its age.

For a lot of this century, iron ore fines with 62 per cent steel from the Pilbara have set the worldwide commonplace – it’s the grade that’s priced, traded, and shipped across the world.

But that benchmark is now beneath strain. As the standard of the fabric slips into decline, pricing company Platts is planning to drop the benchmark to 61 per cent from subsequent yr – a small shift that alerts a greater problem to Australia’s dominance.

High-grade ore is essential because the world shifts from coal-heavy blast furnaces to cleaner electric-arc technology to cut emissions.

Australia needs to steer the inexperienced metal race – Prime Minister Anthony Albanese underscored iron ore’s function in decarbonization during his go to to Shanghai final month – however most Pilbara deposits fall short of the 67 per cent purity usually required, caught between 56-62 per cent.

Closing that hole will demand investing billions in renewables, hydrogen, and processing – no small activity amid weak productiveness and tight funds.

“What got us to this point won’t get us where we need to go,” Tim Day, head of Western Australia iron ore operations at BHP, stated at a June industry occasion within the Pilbara.

“We are playing in a global game, where the rules are changing radically as we speak.”

Australia’s mining giants, together with international chief BHP, nonetheless boast some of the bottom manufacturing prices within the world, with hefty margins.

But the basics are shifting. Future output could rise in quantity, however not in worth. It’s an even greater concern on condition that this income stream is anticipated to bankroll the transition to clean vitality, the one long-term strategic guess the mining majors are at present making.

With wealthy deposits of lithium and uncommon earths, Pilbara miners that constructed their fortunes on crimson filth iron are actually redeploying capital into tasks geared toward powering the vitality transition and assembly hovering demand from knowledge facilities and tech industries.

But earnings from these ventures stay a fraction of iron ore earnings, and the investment dangers stay vital.

After more than a decade on the sidelines, Rio Tinto is back in dealmaking mode, betting huge on the longer term of battery metals.

Its $US6.7 billion acquisition of Arcadium Lithium final yr positioned the miner for a greater function within the international lithium provide chain. The timing, nonetheless, isn’t superb – costs stay mired in a downturn, and Rio is at present revising the fee of its Jadar lithium project in Serbia.

BHP has additionally turned to strategic dealmaking to reshape its future. The world’s biggest miner launched a daring $US49 billion takeover bid for Anglo American final yr, pushed largely by a need to secure more copper, a steel important to the worldwide electrification push.

While the bid finally failed, it signalled BHP’s intent to pivot more aggressively towards various growth-drivers.

Despite the growing momentum behind battery metals, China stays firmly in control of the availability chain and is more likely to for years to come back.

Lithium, copper, uncommon earths and different key inputs to the vitality transition at present generate solely a fraction of the income that iron ore has delivered for many years.

Annual iron ore exports have been estimated at $116 billion in latest authorities knowledge, in contrast with $13 billion for copper shipments and $4.6 billion for lithium.

“Critical minerals are important to Australia’s economy, diversified commodity portfolio and Net Zero plan ambitions, but are not a viable alternative for iron ore,” stated Caroline Tiddy, a geologist and affiliate professor on the University of South Australia.

Fortescue founder and billionaire Andrew Forrest is one of the industry’s loudest advocates for inexperienced technology, and has warned the Pilbara dangers turning into a “wasteland” if Australia fails to adapt to shifting international demand.

Rio Tinto’s incoming CEO Simon Trott, at present head of its iron ore division, stays more sanguine, arguing the area will anchor the financial system for generations.

The reality probably lies someplace in between.

Meanwhile, exterior threats to the Pilbara keep mounting.

Beyond the problem of changing iron ore and dealing with declining grades, US President Donald Trump’s tariffs are already threatening broader international demand. Rivals like Brazil’s Vale are ramping up output and supplying higher-grade ore, intensifying aggressive strain.

Simon Trott has his work cut out. As he prepares to take the helm of the world’s high iron ore exporter on August 25, he struck a assured tone simply days earlier than opening the new Western Range mine.

“Iron ore in the Pilbara will be continuing long after I’m gone – and long after my children’s children have gone,” Mr Trott stated in an interview.

“The Pilbara will last for many decades to come.”

Bloomberg.

Stay up to date with the latest news within the Australian markets! Our web site is your go-to source for cutting-edge financial news, market trends, financial insights, and updates on native trade. We present each day updates to make sure you have entry to the freshest info on Australian stock actions, commodity costs, currency fluctuations, and key financial developments.

Explore how these trends are shaping the longer term of Australia’s financial system! Visit us recurrently for probably the most partaking and informative market content material by clicking right here. Our fastidiously curated articles will keep you knowledgeable on market shifts, investment methods, regulatory modifications, and pivotal moments within the Australian financial panorama.